The

hardest thing to see is what is in front of your eyes.

In my long-ago undergraduate days in western Kansas

students commonly worked deciphering the stratigraphy of the Cretaceous Dakota and/or Kiowa formations. If you did not want a project

in the limestones or chalk beds, then the Dakota/Kiowa was about the only possibility

within close driving distance. In fact,

my senior project was tying to map crossbeds in the Dakota and describing some

sections. I remember the rock colors of

the Dakota were mostly red or orange (or so it seems). We usually described the non-quartz and -calcite

visible minerals as iron oxide or limonite and moved on from there.

|

| These large concretions (~10-12 feet) have eroded from the Dakota (maybe Kiowa) in Ottawa County, Kansas at Rock City. |

As life progressed, I simply thought all red

or orange “stuff” in these sandstones was limonite or some such iron oxide—who cared

about trivialities?

Only later in life

when my first teaching assignment included Sedimentary Geology did I “start to

care,” at least a little! BTW, teaching sedimentary

geology was a joy since originally, I was assigned Structural Geology, a course

that was not one of my strong points ( have you ever tried working with, and understanding, stereonets).

|

| A stereonet is a powerful method for displaying and manipulating the 3-dimensional geometry of lines and planes (www.sciencedirect.com)--or so they say, not so much for me! |

Along with Sedimentary Geology I labored big time in Ground Water

Resources in Western Kansas (I had never taken any sort of a ground water

course), Invertebrate Paleontology, and Intro to Geology. Yep, four different course preps for a kid

who was trying to finish his Ph.D. dissertation and was soon to be a new

father. Spring semester was about the

same with Historical Geology, Intro to Geology, Field Methods, and something

else. I finished the first good draft of

my dissertation on a dark midnight in mid-February and my son was born the next

day. I have trouble, even today,

remembering much of that first academic year, 1970-71, except the pay was $9000

for the academic year and no commitment for a second year. However, things were going my way when a new tenure-track

contract came in mid-May just as the three of us were heading to Dinosaur National

Monument where I had a summer position.

Life was good and I did graduate that summer (although the Park Service

would not let me miss a day to attend graduation in Salt Lake City). After that hectic year I resumed remembering “things.”

The reason my memory was recently jogged about iron

oxide minerals is that Mr. Rockhounding the Rockies (rockhoundingkw.blogspot.com), one of the premier collectors

of minerals from the Pikes Peak Batholith (age around 1.08 Ga) gifted me an absolutely gorgeous

specimen of goethite, an iron oxide-hydroxide [FeO(OH)]. It reminded me, again, that not all iron

oxides/hydroxides look like rust, appear as a coating of clay (as in limonite),

attract a magnet (magnetite), are a critical ore of iron (hematite), nor do

they all come from sedimentary rocks.

In our basic chemistry/physical

geology courses we learned that iron occurs in two different oxidation states:

1) ferrous iron has a plus 2 charge (written as Fe++ or Iron II )

and needs to share two electrons with oxygen to form a neutral ion; 2) ferric

iron has a plus 3 charge (written as Fe+++ or Iron III) and needs to

share three electrons with oxygen to form a neutral ion. Ferric iron is more stable than ferrous iron, the latter then commonly is oxidized (adds more oxygen) and becomes ferric iron.

|

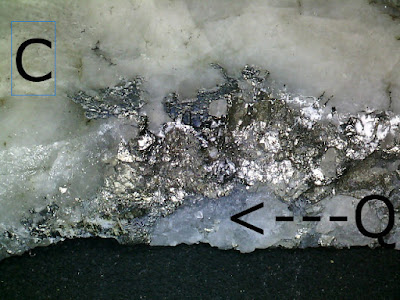

| Photomicrograph of a 1.0 cm. width FOV section of above. Individual prismatic crystals are east to observe. |

Ferrous oxide is rare as

a mineral due to its lack of stability and about the only mineral is wustite, a

rare oxide usually found in meteorites and man-made slag from smelters. The cation iron has a ++ oxidation state

(plus 2) and the anion oxygen has a - - (minus 2) oxidation charge so they

balance out: one iron (++) combined with one oxygen (- -) = FeO.

The major ferric iron

mineral is hematite, Fe2O3. Here you can see two units of iron (charge of

+++) X 2 = 6 combine with three oxygen units (charge of - -) X 3 = 6 or +++ X 2 irons = 6 and - - X 3 = 6 oxygens. So, it balances.

There also is a major iron

oxide mineral termed magnetite, Fe3O4 that appears not to balance! However, magnetite is actually composed of

both ferric and ferrous iron and should be written as: FeO-Fe2O3,

one part of each (one unit of ++iron (2) and two units of +++ iron (6) =

8. One unit of - - oxygen (2) and three

units of - - oxygen (6) = 8. Wow, it

balances.

Iron minerals become even

more complicated when one considers the iron hydroxides where the OH ion with a

charge - - (minus 2) combines with iron.

As far as I can tell, ferrous (Iron II) can combine with a hydroxide ion,

but only as a solution in the lab: Fe++(OH)2. One iron ++ and two hydroxides

- . So, one iron ++(2) combines with two

hydroxides - -(2) and it balances.

Ferric (+++ or Iron 3)

iron may combine with hydroxide to form a really rare and complex mineral

called bernalite [Fe(OH)3]: One Fe+++ (3) combines with three

hydroxides each with a charge of minus 1– to equal 3, and it balances.

Another major group of

iron and oxygen minerals are the Ferric (Iron III) oxide-hydroxides: ferric

iron plus the hydroxide ion plus oxygen.

The major mineral in this group is goethite, FeO(OH). In goethite there is one unit of ferric iron

with an oxidation state of +++ that combines with one oxygen (oxidation state

of - -) and one hydroxide (oxidation state of -). So, three of iron equals the two of oxygen

plus the one of hydroxide, 3 = 3.

In reality, there are at

least three named polymorphs of goethite---exact same chemical formula but crystallizing

in different crystal systems: akageneite, lepidocrocite and feroxyhyte.

But, what about limonite,

that rusty clay or black streak or “ironstone” or whatever that is common in

the orange or red Dakota Sandstone of my youth.

Is the mineral ferric or ferrous iron and is it an oxide, or a hydroxide

or an oxide-hydroxide? It turns out that limonite is not even a mineral [often

written as Fe+3O(OH)-nH2O] but a combination of several

“real” minerals---goethite, lepidocrocite, akaganeite, maghemite, hematite,

pitticite, and “jarosite group” minerals and the term is used “for unidentified

massive hydroxides and oxides of iron, with no visible crystals, and a

yellow-brown streak” (MinDat.org).

Commonly, limonite is composed of goethite.

I am still not certain

that I can identify goethite from limonite in many orange to red sedimentary rocks

since both have similar colors (red, reddish brown, yellow brown, brownish black),

similar hardness (5.0-5.5 or 4.5-5.0 in limonite[Mohs]), dull to metallic to

adamantine luster, and a yellowish brown to orange-yellow streak, and often

massive. However, the goethite

from the rocks of the Pikes Peak Batholith is different in that it often forms

spectacular crystals.

The Pike Peaks goethite

is composed of slender, flattened crystals that are elongated along the C-Axis,

vertically striated, and exhibit a metallic luster. They form “clumps” of radiating crystals and

appear to be black or brownish black in color.

However, the streak is brown to brownish yellow to yellow orange. The crystals are secondary in nature and are

derived by weathering (an oxidizing environment) of many different iron-bearing

minerals. Mr. Rockhounding the Rockies

has collected his goethite specimens from the same cavities that produce

amazonite and smoky quartz (see his web site for many photos).

To learn more about

goethite, and especially Goethe, check out my Blog posting on April 23, 2012: Goethite, Goethe, and

Kaninchen.

And finally, words of

advice from Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832): Every day we should hear

at least one little song, read one good poem, see one exquisite picture, and,

if possible, speak a few sensible words.

The hardest thing to see

is what is in front of your eyes. See top of article. Johann

Wolfgang von Goethe