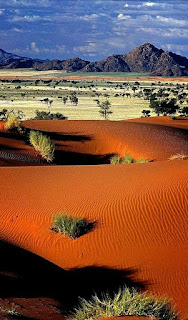

THE DESERT

Hot Kalahari

Mining dark black

manganese

Finding pink

olmiite

This

last fall I was able to purchase, at a great price, several back issues of

Rocks and Minerals, issues starting before my subscription begin. I enjoy, immensely, reading the journal from

cover to cover. The May/April 2012 issue

had, as its cover photo, a specimen of olmiite, a newly discovered mineral

(2007) from the N’Chwaning Mine II, Kalahari manganese fields, Republic of

South Africa. I thought the mineral and photo were pretty spectacular and decided to look for such while touring

the Tucson Shows in February. I was

always peering at the different booths and tables and was about ready to admit

defeat when there it was, olmiite in a perky box on a table with many other

thumbnails. The proprietor told me he wasn’t

certain what olmiite was except a manganese mineral. He originally had two specimens but had sold

one and since the show was drawing to a close I could have it for half price,

$7. I grabbed it out of his hand and

handed him the cash. At least it seemed

like a good deal to me.

The photo that started it all!

I

was interested in the mineral, not only for its good looks, but also due to its

rarity. According to MinDat most olmiite

specimens on the market have from the N’Chwaning Mine II, the Type Locality,

but a few specimens are known from the nearby Wessels Mine (four photos in

MinDat) and N’Chwaning III Mine (one photo in MinDat). Olmiite is also listed

by MinDat as being found in the Långban Mine (no photos) in Sweden. For a little interesting trivia, note that

the iron ore and manganese mining at Långban has produced ~300 different minerals and is the Type

Locality for ~60!

The

Kalahari, home to the N’Chwaning and associated mines is

the world’s most prolific producer of manganese (and also home to a famous

desert). The deposits are in the Hotazel Formation of Proterozoic age

(Precambrian) and are the largest land-based (deep sea deposits are larger but

nearly impossible to mine) sedimentary manganese deposits in the world, perhaps

covering ~425 sq. miles. The ore has been subjected to both hydrothermal

alteration (temperatures up to 450°C) and to metamorphism. The origin of the

giant manganese deposits has been debated for many years but remain

controversial: “Proposed models cover a diverse spectrum of genetic processes,

from large-scale epigenetic replacement mechanisms, to submarine

volcanogenic-exhalative activity, to purely chemical sedimentation whereby the

influence of volcanism is of reduced significance” (Tsikos and Moore,

2006).

Olmiite, CaMn++[SiO3(OH)](OH), is best known for its reddish pink color (pale to intense) but also occurs in various shades of raspberry, honey, pinkish tan, white to gray, while the crystals at N’Chwaning III are gemmy clear and some at Wessels are translucent clear. However, the reddish pink is the color that sticks in the minds of collectors.

Olmiite with white crystals of bultfonteinite. Width FOV ~1.3 cm.

Orthorhombic olmiite, a product of hydrothermal alteration, is transparent, has a vitreous luster and a white streak; hardness is ~5.0-5.5 (Mohs). Crystal habits include prismatic, spherical radial bundles, crystal sprays and what has been termed wheat-sheaf-like aggregates. The olmiite in my collection, as do most other olmiite specimens, has a deep red fluorescence under short wave UV.

My specimen of olmiite, as do many others, is associated with a little-known

mineral (at least to me) named bultfonteinite, a

fluorine bearing calc-silicate---Ca2(HSiO4)F-H2O.

Calc-silicates are rocks, or their composing minerals (common minerals include

diopside, wollastonite, the “garnets” grossular-andradite, and epidote) that

usually form in high-temperature, contact metamorphic zones where a mafic magma

(high magnesium and iron content, low silica content) intrudes into limestone

or other carbonate rocks, as in a skarn. The Type Locality of bultfonteinite is at the famous diamond-bearing kimberlites

in present-day Kimberley, Northern Cape, South Africa. Bultfonteinite was

first found in a large, isolated block of dolerite (an igneous rock like

basalt)) and shale fragments that were enclosed in a kimberlite pipe. These

pipes consist of an igneous rock known as peridotite (lots of iron, silica, olivine,

amphibole, magnesium) that form deep within the earth’s mantle and then

rapidly and violently eject to the surface. Evidently the ejecting pipe

picked up this large hunk of dolerite and shale on its way to the surface. In the U.S. bultfonteinite is uncommon but

is found in the famous calc-silicate rocks from the Crestmore Quarries in

California.

Prismatic acicular crystals of bultfonteinite associated with olmiite shown above. Width FOV: top (spray) ~1.5 mm, middle ~1.1 cm, bottom ~1.0 mm.

Bultfonteinite is usually found as small, transparent, colorless to pale pink or white, radiating prismatic acicular crystals. Crystals are vitreous, have a white streak and a hardness of ~4.5 (Mohs). They seem to look like many other white acicular globs of crystals I have seen since beginning my quest for nifty micromounts and thumbnails.

REFERENCES

CITED

Cook, R. B., 2012, Connoisseur’s Choice, Olmiite: Rocks and

Minerals, Vol. 87, No. 2.

Tsikos,

H. and J.M. Moore, 2006, The chemostratigraphy of a Paleoproterozoic MnF- BIF succession

-the Voelwater Subgroup of the Transvaal Supergroup in Griqualand West, South

Africa: South African Journal of

Geology, v. 109.

.png)