The

November 19, 2019, posting described minerals, especially philipsbornite and

osarizawaite, collected from the Grandview Mine located on Horseshoe Mesa

within Grand Canyon National Park (GCNP). The

Mine had a long history of producing copper, and attracting visitors, until

purchased and annexed into the Park in 1940.

Specimens continued to appear from the Mine (collected illegally) until “bat

gates” closed the entrance in 2009.

I

have now acquired a second specimen, halotrichite (originally in the collection

of David Shannon, noted Arizona rockhound), collected from a mine near Grand

Canyon Village in the Park—the Orphan (Lost Orphan; Orphan Lode) Mine. I am indebted to George Munford of Northern

Arizona University for the information in the paragraph below. See George’s complete story at

intermountainhistories.org.

|

| Hogan built the Hummingbird Trail down to the mine entrance--not for me. Photo Public Domain courtesy of GCNP. |

The

Mine was originally staked as a copper prospect by Danial Hogan (maybe with

Henry Ward as a partner?) in 1893 and then Hogan upped the ante by filing a patented

claim with Charles Babbitt in 1906. The

Mine was never a large copper producer and continued to struggle in the early

1900s. This struggle was compound in

1919 when the Mine was incorporated into the new National Park. By the late 1930s Hogan saw a new opportunity

for his land and invested in building the Kachina Lodge for tourists. But more troubles

hit Hogan as World War II essentially stopped the flow of visitors to the

Park. He ended up holding onto the claim

until finally selling it in 1946, without ever hitting the big bonanza. The new owners (several of them) continued

struggling until rich uranium ore was discovered in 1951. “Big Mining companies”

then moved in with money, purchased the claim, started mining, and greatly

expanded the business during the “cold war” and uranium boom. Western Gold and

Uranium, Inc. (the owners) built a tramway from the south canyon rim down 1800

feet where the Mine entered the side of the canyon wall. Ore was transported up to the rim and then

hauled to a processing plant in Tuba City, AZ. On May 28, 1962, President John

Kennedy signed into law, Public Law 87-457, which permitted Western Equities,

Inc. to mine uranium ore in Grand Canyon National Park, adjacent to the Orphan claim,

in exchange for title to the claim in 25 years (1987) . The law specified that

all mining would be underground and that the tram would be dismantled by 1964.

The Federal Government would receive a royalty ranging from 5 to 10 percent on

the ore produced (Chenoweth, 1986). The

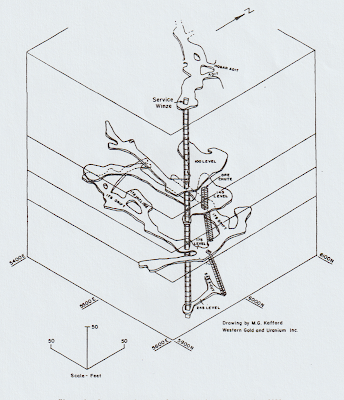

tram was dismantled, and a 1500 foot shaft was drilled straight down from the

rim and an elevator was installed.

|

| The tramway ran from the rim to the mine, 1800 feet of cable. Book may be ordered from Grandcanyonorphan.com |

For

those of us in Colorado it is interesting to note that in 1967 the Orphan claim

and related properties were sold to the Cotter Corporation of Roswell, New Mexico,

and Canon City, Colorado. During 1967, the Cotter Corporation enlarged its mill

at Canon City to process 400 tons per day in an alkaline leaching circuit and

100 tons per day in an acid circuit. A flotation cell was added to remove iron

and copper sulfide minerals from the ore prior to alkaline leaching. The first

ore was loaded for Canon City on rail cars at an Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe

Railway Company's siding in Grand Canyon National Park on September 27, 1967.

Since Cotter's AEC contract had expired on February 28, 1965, all uranium

produced after that date was sold on the private market to electrical utilities

(Albrethsen and others, 1982).

By

1969 the mine had produced nearly 500,000, tons of ore that yielded about 4.2

million pounds of uranium oxide. By then Mine owners were going bankrupt due to

rising production and transportation costs, and federal regulations. The

National Park Service finally acquired the abandoned mine and surrounding acres

in 1987.

As

with many mines in the West, bankrupt owners left U.S. taxpayers a cleanup bill. The Orphan Mine was declared a Superfund Site

due to contamination by the uranium and we shelled out 15 million bucks to remediate

the site. Even today uranium mining

companies want to mine near the Park and a wide variety of groups and citizens

continue to fight this proposition. In

2012, the Secretary of the Interior issued a 20-year temporary ban on exploration

for new uranium mines (currently 831 active mining claims) on one million acres

of public lands surrounding the Grand Canyon National Park. Rep.

Raúl Grijalva (R-AZ) introduced the Grand Canyon Centennial Protection Act to

ban new uranium mines around Grand Canyon National Park forever. The bill

passed the U.S. House of Representatives on October 30, 2019. On December 19, 2019, Sen. Kyrsten (D-AZ)

introduced a companion bill, S-3127, in the U.S. Senate; it is awaiting action.

Early

reports on the Orphan Mine by Max G. Kofford, chief mine geologist for Golden Crown

and Western Gold and Uranium, attributed its origin to a cryptovolcanic

structure or diatreme. However, as with the Grandview Mine previously

described, the minerals at the Orphan Mine are concentrated in breccia zones

situated alongside structural flexing features.

The ore bodies are a pipe-like structures entirely hosted in the upper

Redwall Limestone and are associated with the Breccia Pipe Uranium District

described by Wenrich and others (1992, 2018).

They noted “the northern Arizona

metallic district can be thought of as a paleo-karst terrain, pock-marked with

sink holes, where in this case most “holes” represent a collapse feature that

has bottomed out over 3000 ft (850 m) below the surface in the underlying

Mississippian Redwall Limestone. These breccia pipes are vertical pipes that

formed when the Paleozoic layers of sandstone, shale and limestone collapsed

downward into underlying caverns.” The

base-metal ores (copper and silver) may be related to, or similar to,

Mississippi Valley Type deposits where emplacement of ores suggest low

temperatures (as opposed to hydrothermal emplacement). Perhaps even more interesting in today’s

geopolitical world is that Rare Earth Elements (REEs), and especially Heavy

Rare Earth Elements (HREEs), are significantly enriched in the uraninite (UO2)

found in many breccia pipes. “Mixing of

oxidizing groundwaters from overlying sandstones with reducing brines that had

entered the pipes due to dewatering of the Mississippian limestone created the

uranium deposits” (Weinrich and others, 2018).

I wonder if REEs are also present at the Orphan?

|

| Halotrichite crystals/fibers on matrix. Width FOV ~9 mm. I remain uncertain about the golden/yellow grains and the black grains; they may be some of the uranium minerals. |

So,

the lonely mineral I have from the Orphan is halotrichite, a hydrated iron

aluminum sulfate [FeAl2(SO4)4-22H2O].

The mineral is interesting in that it usually appears as acicular or hair-like

fibers that may form tuffs, matted crust-like aggregates, or efflorescence. The colors are usually pastels-white,

colorless yellowish, greenish and crystals are quite soft at ~1.5 (Mohs). They have sort of a silky luster and are water

soluble. Halotrichite may precipitate around hot springs and volcanic fumaroles

or form as efflorescence in weathering sulfide deposits and oxidizing pyritic

coals.

REFERENCES CITED

Albrethsen,

Holger, Jr. and F. A. McGinley, 1982, Summary history of domestic procurement

under U.S. Atomic Energy Commission contracts, final report: U.S. Department of

Energy, Open File Report GJBX-220(82).

Chenoweth,

W.L.,1986, The Orphan Lode mine, Grand Canyon, Arizona, a case history of a

mineralized collapse-breccia pipe: USGS Open File Report 86-510.

Weinrich,

K. J., G.H. Billingsley, and B.S. van Gosen, 1992, The potential of breccia

pipes in Mohawk Canyon area, Hualapai Indian Reservation, Arizona: U.S.

Geological Survey Bulletin 1683-D.

Weinrich,

K.J., P. Lach, and M. Cuney, 2018, Rare-Earth elements in uraninite-Breccia

Pipe Uranium District Northern Arizona in Delventhal, E. (ed), Minerals from

the metallic ore deposits of the American Southwest symposium: Friends of

Mineralogy-Colorado Chapter.

A LITTLE TIDBIT

In

the late 1950s, the mining company believed the uranium lode extended beyond their

claim into federal property. In what appears

to be some muscle, the company proposed building an 18 story, 800 room hotel overhanging

the rim. This grand hotel would spill “down the side of the precipitous cliff

like a concrete waterfall” ending at a swimming pool and sun deck below. The mining company thought that the public

would much better like a small uranium mine in their Park rather than a giant

hotel. Put some pressure on the Park

Service!! The compromise was the 1962

Kennedy Law with the hotel taken off the drawing board. Photo above courtesy of GCNP.

Not all holes, or games, are created equal. George Will